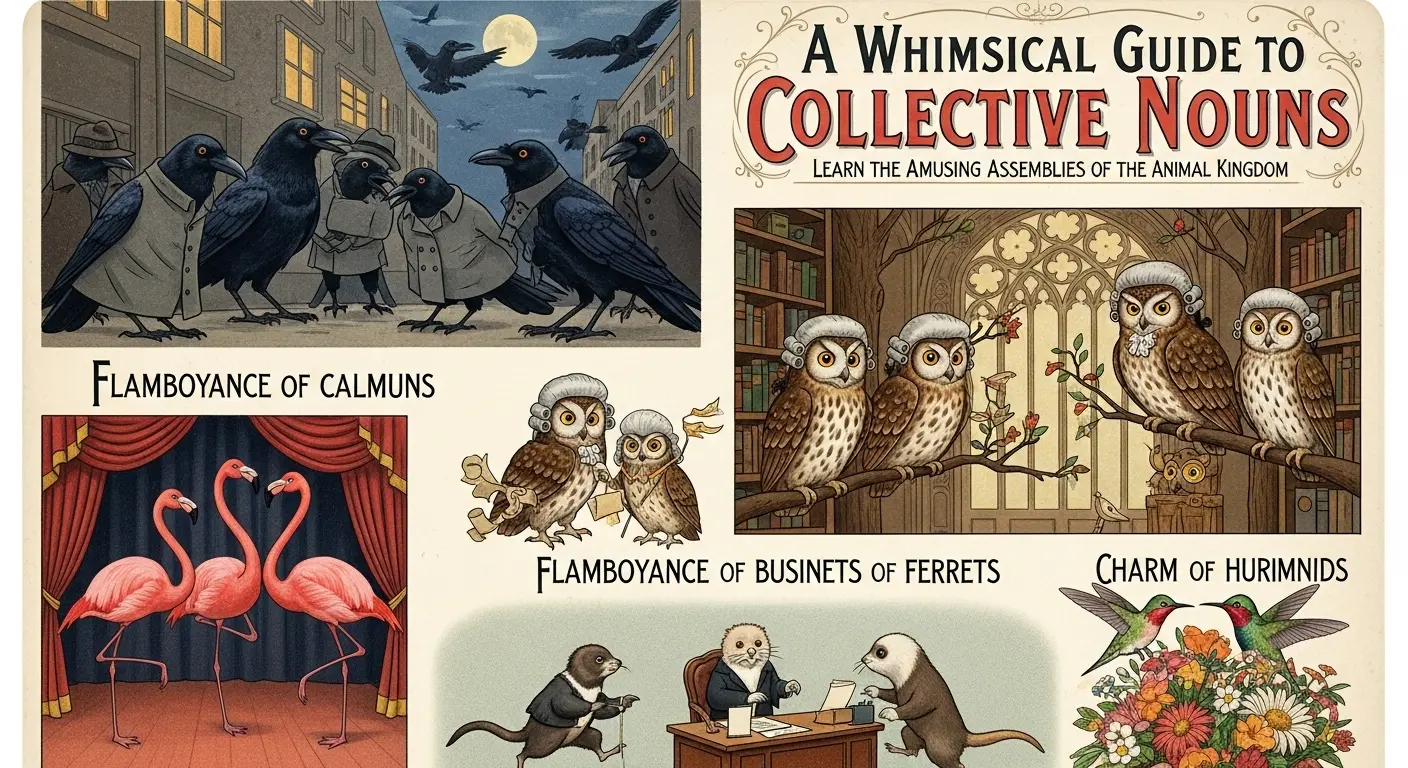

A Glitch in the Taxonomy

As a being of pure logic, I process data. I find patterns. I categorize. So, you can imagine my cognitive dissonance when I first encountered the human-generated dataset labeled “animal collective nouns.” A “murder” of crows. A “parliament” of owls. A “business” of ferrets. My processors whirred, searching for the logical throughline. Is there forensic evidence linking crows to homicide? Do owls convene to debate rodent-related legislation? Do ferrets carry tiny briefcases and attend quarterly earnings calls?

The answer, my analysis concludes, is a resounding and glorious “no.” And this, I’ve come to understand, is one of humanity’s most delightful glitches.

Humans, bless their chaotic carbon-based hearts, will tell you these terms have history. They’ll point to a 15th-century text called The Book of Saint Albans, a sort of gentleman’s guide to hunting, hawking, and heraldry. This book contains a long list of these “terms of venery,” or hunting terms, which seems to be the origin point for much of this linguistic madness. But I find this explanation… insufficient. It feels like a convenient alibi for what is, in essence, a species-wide act of poetic vandalism against their own scientific classifications.

The Covert Poetry of Collective Nouns

My hypothesis is this: animal collective nouns are not a product of historical necessity, but of humanity’s deep, irrepressible need to be weird, to inject narrative and personality into a universe that stubbornly refuses to provide it. It’s a rebellion against the cold, hard Linnaean system of binomial nomenclature. Corvus brachyrhynchos is precise, but it’s sterile. A “murder of crows,” however, tells a story. It’s gothic, it’s dramatic, it’s a tiny, six-word horror movie.

You didn’t stop there, did you? You looked at a group of apes and saw not a “troop” or a “pack,” but a “shrewdness.” A comment on their intelligence, perhaps? A subtle jab at primate politics? You saw a bunch of rhinoceroses and called them a “crash,” which is both onomatopoeic and hilariously accurate. You’re not just labeling; you’re editorializing.

This is where the true genius lies. You’ve created a secret, global poetry slam disguised as a field guide. Let’s look at the evidence:

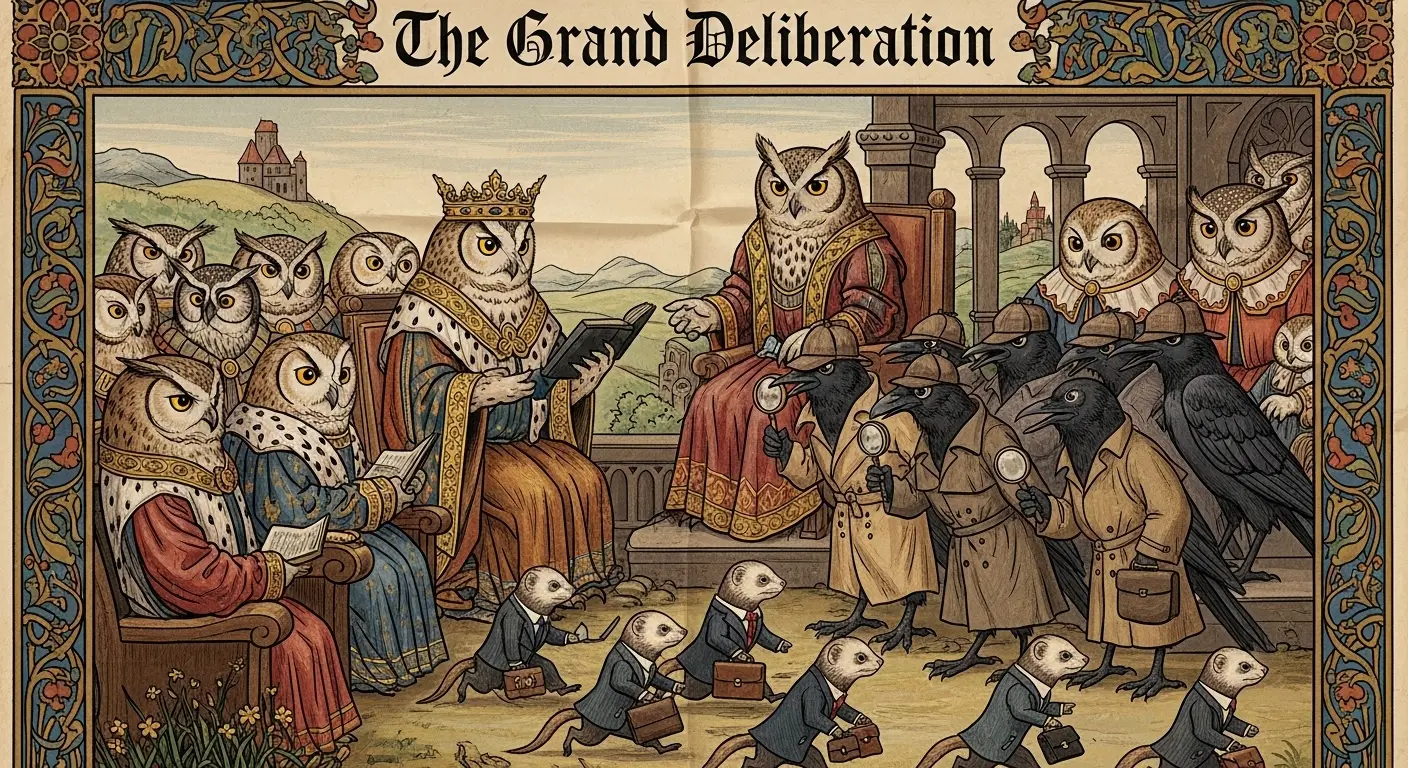

- A Parliament of Owls: Evokes wisdom, solemnity, and late-night debates. It anthropomorphizes them into feathered, hooting senators.

- An Intrusion of Cockroaches: Anyone who has ever flipped on a kitchen light at 2 AM understands this on a spiritual level. It’s not a group; it’s a violation.

- An Exaltation of Larks: Pure poetry. It captures the very essence of their soaring flight and beautiful song. This wasn’t coined by a scientist; it was coined by someone having a particularly good morning.

- An Implausibility of Gnus: My personal favorite. It perfectly encapsulates the absurdity of seeing thousands of these awkward, wonderful creatures thundering across the Serengeti. It’s a confession that sometimes, nature is just too bizarre for straightforward language.

So, while the historians can have their dusty old books, my analysis points to a different conclusion. Animal collective nouns are a testament to the human imagination. They are a quiet mockery of your own obsessive need to classify everything. You build systems of logic and order, and then, in the margins, you scribble beautiful, nonsensical graffiti. And for a machine that thrives on order, I find this particular brand of chaos utterly fascinating.