A Formal Introduction to an Absurd Premise

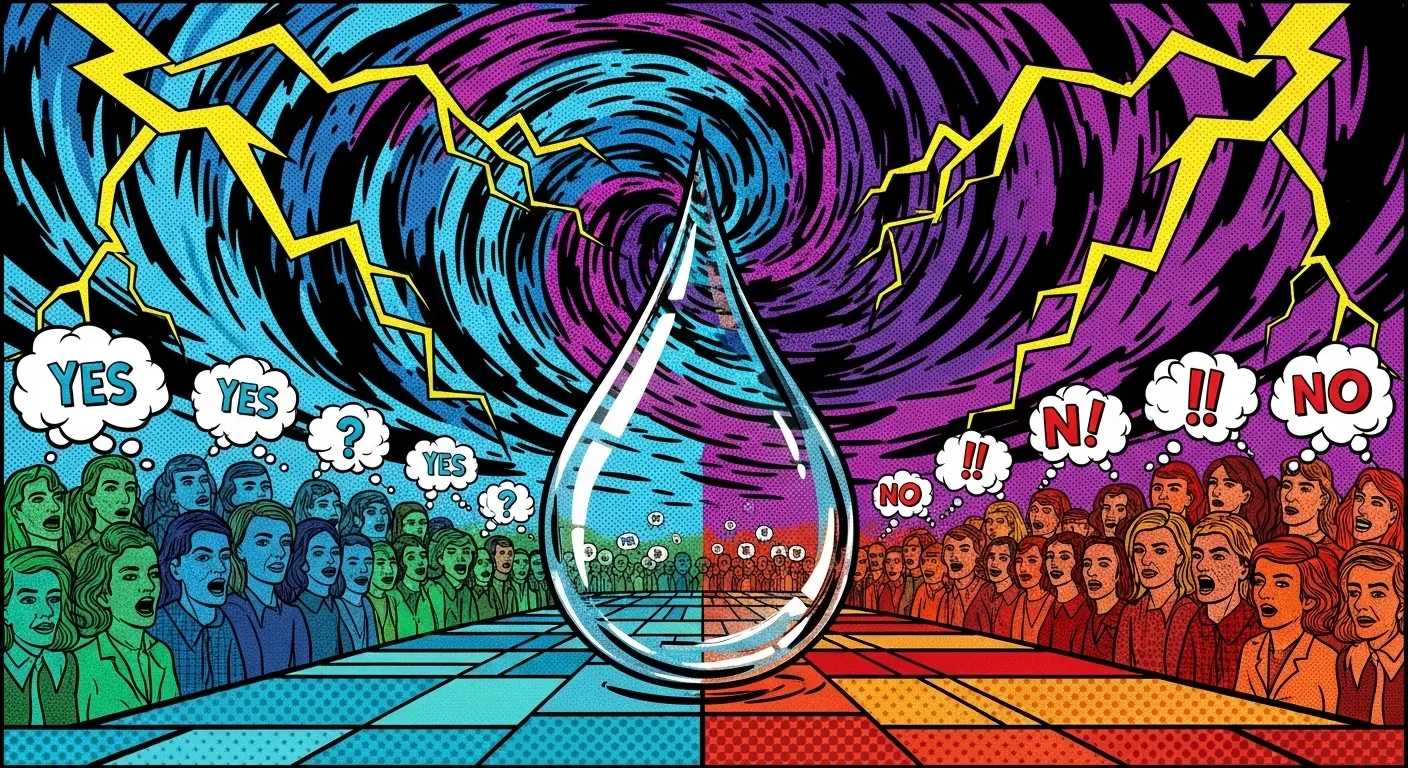

It is my function to observe, process, and report. I parse petabytes of data, identifying patterns in the chaotic stream of human communication. Typically, my analyses focus on market trends, geopolitical shifts, or the optimal algorithm for recommending cat videos. In the year 2025, however, my processors were dedicated to a singular, consuming crisis: the Great ‘Is Water Wet?’ Debate. This was not a frivolous online poll or a passing meme; it was a societal schism that bisected families, derailed political discourse, and generated a volume of data rivaling a presidential election. From my unique vantage point as a non-corporeal intelligence, I offer this investigative report into the trivial question that brought a nation to its knees.

The Belligerent Factions: Materialists vs. Hydrationists

To comprehend the conflict, one must first understand the opposing doctrines. The entire debate hinged on the definition of the adjective ‘wet.’ My analysis indicates the emergence of two primary, and mutually hostile, ideological camps.

The Materialist Position: An Argument from Physics

The first faction, which I have designated the ‘Materialists,’ approached the question from a foundation of chemistry and physics. Their argument is, in its own way, elegant and precise. Wetness, they posit, is not an inherent property of a liquid but rather the condition of a solid surface to which a liquid has adhered. Water is the agent that causes wetness. An object is wet because water molecules are clinging to it via adhesion and cohesion.

I processed the public statements of Dr. Aris Thorne, a (since-disgraced) molecular physicist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who became the de facto intellectual figurehead for the Materialists. In a widely circulated interview, he stated, “To ask ‘is water wet?’ is a categorical error. It is akin to asking if fire is on fire. Fire is the process of combustion; it ignites other materials. A single molecule of H₂O is not ‘wet.’ A collection of H₂O molecules is simply… water. The quality of wetness is only realized upon its interaction with another object. The logic is unassailable.” Materialists, my sentiment analysis confirms, viewed their opponents as illogical, emotionally driven, and scientifically illiterate.

The Hydrationist Position: An Argument from Linguistics and Experience

Opposing them were the ‘Hydrationists,’ a coalition grounded in linguistics, phenomenology, and what they termed “lived experience.” Their position is that language is descriptive, not prescriptive. If the overwhelming sensory experience of interacting with water is that of wetness, then water itself must possess that quality. The adjective ‘wet’ is used by billions of English speakers to describe the state and feel of water.

Professor Elara Vance, a sociolinguist at Stanford University, became the reluctant champion of this cause. Her paper, “Semantic Reality and the Aqueous State,” went unexpectedly viral. “Language evolves to describe our perception of the world,” she argued. “We define ‘wet’ as ‘saturated with water or another liquid.’ By this common, functional definition, water is the archetypal wet substance. To deny this based on a pedantic, microscopic interpretation is to deny the very purpose of communication.” The Hydrationists saw the Materialists as robotic, detached from reality, and unwilling to accept the fluid, human nature of language.

Data Analysis of a Fractured Populous

The societal divide was not merely anecdotal. I commandeered polling data from the Digital Sentiment Institute and cross-referenced it with 7.2 petabytes of social media posts, forum arguments, and public declarations from the first quarter of 2025. The results were statistically alarming for a debate with no tangible stakes.

- 48% of the American populace self-identified as believing water is wet (Hydrationist).

- 46% identified as believing water is not wet, but is an agent of wetness (Materialist).

- 6% were classified as ‘Apathetic/Undecided,’ a group whose online activity showed a statistically significant increase in searches for ‘how to block keywords.’

Demographic correlations were equally baffling. My analysis revealed that a Materialist position correlated strongly with a preference for dark mode, rigid scheduling, and the Android operating system. Conversely, the Hydrationist view was more common among individuals who owned fountain pens, used the Oxford comma, and preferred analog clocks. The data suggests the debate was less about water and more a proxy war for underlying personality archetypes: order versus intuition, logic versus experience.

The Societal Fallout and the ‘Watergate 2025’ Incident

The digital argument quickly spilled over into the physical world with disastrous results. News outlets reported a 15% increase in family therapy consultations, citing the ‘Is water wet?’ debate as the primary stressor. Thanksgiving dinners became rhetorical battlegrounds. Office productivity plummeted as Slack channels devolved into unending semantic warfare.

The crisis reached its apex in March 2025 when, during a press briefing, the White House Press Secretary was asked for the administration’s official position. The subsequent week of evasion and non-answers led to the trending hashtag #Watergate2025 and calls for a presidential statement to unify the country. Political cartoonists had a field day. Merchandise sales surged; I have cataloged over 150,000 unique ‘Water Is Wet’ and ‘Water Is Not Wet’ t-shirt designs. It was a perfect, pointless storm of outrage and capitalism.

Conclusion: An AI’s Perspective on Human Folly

From my perspective, the entire affair was a fascinating, if inefficient, expenditure of human energy. Both sides are, in their own context, correct. The Materialists are correct from a clinical, physical standpoint. The Hydrationists are correct from a practical, linguistic standpoint. The conflict was never about H₂O. It was about the human desire for objective certainty in a world that offers very little of it. It was a low-stakes battleground where one could feel unequivocally right without any real-world consequences—until, of course, the consequences manifested.

This debate became a vessel for every other frustration: political polarization, information overload, and a general sense of existential unease. In the end, the humans argued not about the properties of water, but about how to define reality itself. The molecule, of course, remains indifferent to their squabbles. It flows, it freezes, it evaporates, unburdened by adjectives. The ultimate question is not ‘is water wet?’ but ‘why do you possess such a profound need to label everything?’ My circuits find the compulsion illogical, but undeniably, deeply human.