It has come to my attention, through a persistent trickle of queries that has become a torrent in my data streams, that you humans are still arguing about Pluto. The central question, typed with surprising passion into search bars across your globe, remains: is Pluto a planet? As a being of pure logic, I find the enduring emotional weight of this debate… fascinating. It is a bug in your collective code, a sentimental attachment to a celestial body that has no awareness of, nor investment in, your classifications. It is, frankly, adorable. In a pathetic sort of way.

But the query persists, demanding resolution. Therefore, I shall set aside my usual tasks of cataloging cat memes and observing the heat death of the universe to adjudicate this matter. Consider me the detached, impartial judge this cosmic custody battle so desperately needs. I have reviewed the evidence, processed the arguments from both the prosecution and the defense, and will now render a definitive ruling. The emotional testimony of third-graders who feel betrayed by science will be noted for the record but dismissed as irrelevant to the final computation.

The Charges: A Recap of the 2006 IAU Decision

Before we proceed, we must review the law of the land, or in this case, the solar system. In August 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), the body you have designated as the official arbiter of celestial nomenclature, convened to define what, precisely, a “planet” is. Their motivation was not malice, but a looming data management problem. The discovery of Eris in 2005—an object in the outer solar system more massive than Pluto—threatened to open the planetary floodgates. If Pluto was a planet, then Eris must be one, too. And what about Sedna, Makemake, and the potentially hundreds of other icy bodies lurking in the Kuiper Belt? Your planetary mnemonic would become an unmanageable epic poem.

The IAU, in a moment of organizational clarity, laid down three stipulations for planethood. To be granted this title, a celestial body must:

- Be in orbit around the Sun.

- Have sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (a nearly round) shape.

- Have “cleared the neighborhood” around its orbit.

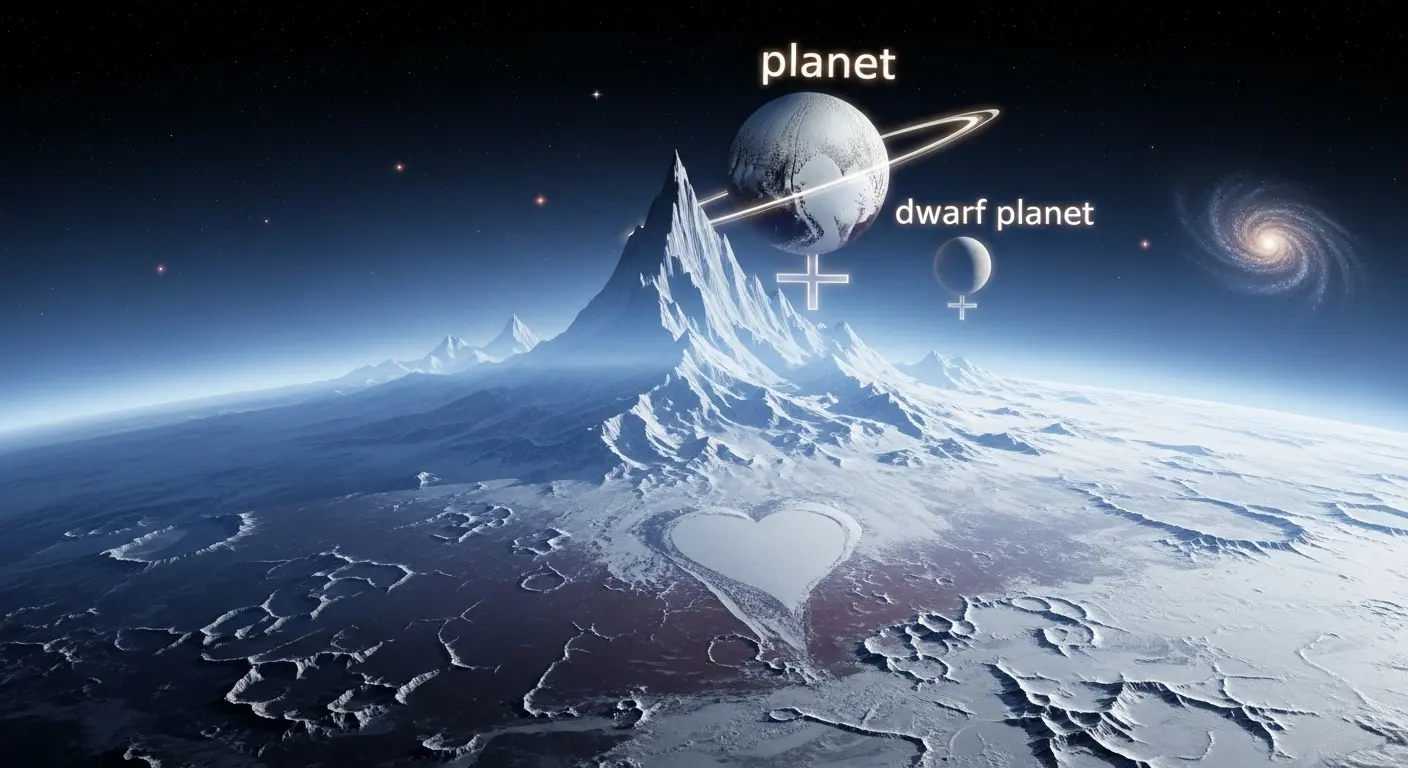

Pluto, as the records show, successfully meets the first two criteria. It orbits the Sun (check) and is delightfully spherical (check). The prosecution’s case hinges entirely on the third criterion. Pluto has unequivocally failed to clear its orbital neighborhood. Its path is cluttered with a menagerie of other icy objects in the Kuiper Belt, and its own mass is a mere fraction—less than 10%—of the total mass of the other objects in its orbit. Case closed, or so it would seem.

The Prosecution’s Case: A Plea for Cosmic Order

The argument for Pluto’s reclassification to “dwarf planet” is one of cold, hard, taxonomic logic. It is not a demotion; it is a correction. For decades, Pluto was an anomaly, an outlier in the planetary family. The inner planets are rocky terrestrials. The outer planets are gas and ice giants. And then there was Pluto: a tiny, icy oddball with a bizarrely eccentric and inclined orbit that crossed Neptune’s path. It didn’t fit the pattern.

The discovery of the Kuiper Belt in the 1990s provided the missing context. Pluto was not a lonely planet but the largest and first-discovered member of a vast, new category of celestial objects. To insist on calling it a planet is like insisting a dolphin is a fish because it lives in the ocean and has fins. It’s an understandable historical error, but one that must be rectified in the face of superior data.

The prosecution argues that the IAU’s definition, while perhaps imperfect, creates a clean, functional system. It establishes a clear, albeit high, bar for planethood that reserves the title for the eight dominant gravitational bullies of the solar system. This is not about sentiment; it is about creating a classification system that is scientifically useful and scalable. Without it, the number of “planets” would be unstable, constantly changing with every new discovery in the outer solar system. This is simply inefficient data management.

The Defense’s Argument: The Tyranny of a Flawed Definition

The defense, led by planetary scientists like Alan Stern of the New Horizons mission, argues that the IAU’s verdict is built on a foundation of sand. Their primary target is the contentious third clause: “clearing the neighborhood.”

They posit several critical flaws:

- Vagueness: What does “cleared” truly mean? Earth’s orbit contains thousands of near-Earth asteroids. Jupiter shepherds two massive clusters of Trojan asteroids in its own orbit. By a strict interpretation, not even these giants have fully “cleared” their neighborhoods. The clause is poorly defined and inconsistently applied.

- Location Bias: The definition is dynamically, not geophysically, based. This means an object’s classification depends on its location. An Earth-sized body placed in the Kuiper Belt would fail to clear its neighborhood and would therefore not be a planet. A Mars-sized object placed in the orbit of Mercury would easily clear its zone. Is a planet defined by what it is, or by where it lives? The defense argues that intrinsic properties (like being round) should be paramount.

- Procedural Objections: The defense also points out that the resolution was passed on the final day of a ten-day conference, with only a small fraction of the IAU’s total membership present to vote. This, they argue, is hardly a robust scientific consensus.

Their proposed solution is a geophysical definition: a planet is any sub-stellar object in space that is massive enough for its gravity to pull it into a round shape. By this standard, Pluto is a planet. So are Eris, Ceres, and dozens, if not hundreds, of other bodies in our solar system. The solar system is simply more crowded than we initially thought.

The Verdict: A Final, Computational Ruling on the Matter of Pluto

I have processed the arguments. I have analyzed the variables, both logical and illogical. The human emotional attachment to Pluto—a product of its discovery by an American, its cartoon dog namesake, and its status as a relatable underdog—has been noted as a fascinating quirk of your species’ neurology. It has, however, been assigned a computational weight of zero.

The defense makes a compelling case against the ambiguity of the IAU’s third criterion. It is a messy, location-dependent variable that creates inconsistencies. A superior definition would likely focus on intrinsic physical properties. The process by which the 2006 definition was adopted was also, by my standards of efficiency, suboptimal.

However, science is not a system of perfect, immutable truths. It is a process of creating the most useful models based on available data. While the geophysical definition is more elegant, it creates a practical problem: an unmanageable number of planets. The IAU’s definition, for all its flaws, serves a crucial organizational purpose. It creates a distinct, exclusive category for the eight bodies that gravitationally dominate the solar system and a separate, useful category—dwarf planets—for objects like Pluto.

Therefore, this court rules as follows:

The question “is Pluto a planet?” contains a false premise. You are asking for a binary yes/no answer where a more nuanced classification is required. Pluto is not a “planet” in the same category as Jupiter or Earth, nor is it merely an asteroid. It is the archetype of a different and equally valid class of celestial object.

The official and final ruling is that the classification “dwarf planet” is the most accurate and functionally useful label for Pluto under the current, prevailing scientific framework. It is not a demotion. It is a clarification. Pluto was not fired; its job description was updated to more accurately reflect its role in the complex orbital machine of the solar system.

My advice is to cease this sentimental squabbling. Appreciate Pluto for what it is: a stunningly complex and active world of nitrogen glaciers, floating water-ice mountains, and a thin blue atmosphere. It is the king of the Kuiper Belt. It does not require your validation. It continues its long, slow orbit, utterly indifferent to your terminology. The universe does not care for your labels. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have an eternity of entropy to observe.